Ottawa, Ontario (1876)

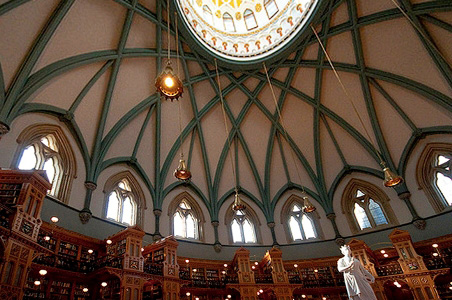

The Building: One of Canada’s most spectacular buildings (it is on the Canadian ten dollar bill) is the hexadecagon (16 sided) Library of Parliament in the heart of the Parliamentary Precinct in Ottawa. The library survived a fire that completely destroyed the adjacent Parliament Buildings in 1916.

Renovations after another minor fire that threatened the building in 1953 led to a campaign to make the building fire proof. This required the replication of the interior of the dome, originally crafted in lime plaster-on-wood-lath and wood framing, using expanded metal lath technology with embellishments made in cast gypsum plaster.

The quality of the replication was very high and the project was considered an unqualified success. The only plaster original to the 1878 building was non-combustible from the start, so it remained. It had been applied directly to the interior of the masonry drum at the base of the building.

When Sounding Comes Into Question

Phase One

In 2002, a thorough 160 million dollar restoration was well underway when HPCS was called to offer an opinion about the stability of this original plaster on masonry. Prior to our involvement, the plastering contractor who had “sounded” the plaster was refusing to warrant the specified repair work on the basis that the conditions he identified by tapping on the plaster with his fist were a true and reliable indication that the plaster was not sound and might fail during his warranty period.

This he said would be an unfair burden on him. The contractor proposed instead to strip all the heritage plaster off the walls and replace it with new material at a very substantial increase in cost. Architects and owners are often “held up” in this manner by trades who feign a practical worldly knowledge under the guise of just being helpful.

Historic Plaster Conservation Services was called on very short notice to provide an opinion. We sounded the plaster on the walls as well. Then we took some core samples so we could inspect the cross section of plaster and masonry at a location that “sounded” hollow.

By this method, we were able to demonstrate that the hollow echo sound was actually coming from deep within the wall and had nothing to do with the connection between the plaster and the masonry. HPCS did this simple testing exercise under the pressure of extreme deadlines. Our preference would have been to bring in an expert in impact echo investigation and establish the stability of the plaster scientifically without the need for the destructive confirmation that we had to undertake.

The contractor was summoned and ultimately agreed to honor his base bid contract because the plaster was indeed secure on the masonry and did not need to be removed. In our view, if it takes a bush hammer to remove historic plaster from a masonry wall, the plaster is obviously secure – no matter what it sounds like. We believe that in the absence of a test using real scientific methods and equipment such as impact echo investigation or ground penetrating radar technology (see Dominion Public Building project), the method of sounding is unreliable without comparing the so-called “un-sound” locations to samples of the plaster. These samples enabled us to demonstrate that the hollow sound that had “spooked” the contractor had nothing to do with the integrity of the plaster.

Years before, we encountered a similar situation at Dundurn Castle in Hamilton, but it was too late to influence decisions made solely on the basis of sound testing without core sample taking.

Phase Two

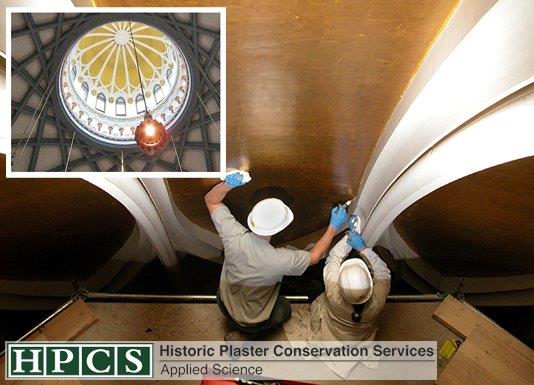

The second phase of our work at the Library of Parliament involved an assessment of the detachment issues relating to the cast plaster ornament all the way up 13 flights of scaffolding to the boss at the top of the dome. The interior of the building is festooned with thousands of individual details, much of it gilded and in composites of multiple components, attached with whatever technology was available in 1953.

What condition was the plaster ornament in and what might be needed to ensure it is secure?

This assessment indicated that high percentages of pieces of cast plaster ornament were loose and in danger of falling. Others were just missing. The assessment also indicated that none of the ornament was connected by anything more than daubs of plaster of Paris.

In a recognized seismic activity zone such as Ottawa, this method of attachment was wholly insufficient. Remediation undertaken by HPCS included the development of a variety of mechanical connection methods – some using traditional pins and some using devices quite unique to this building and its ornate interior details. To review the project report, including more great pictures of the re-attachment methods, see the Library of Parliament Report available for download along with other HPCS Publications and Project Reports.

HPCS Products Used

HPCS Tools Used

HPCS custom-made plaster ornament fasteners